East Saint Louis is in Illinois, just across the Mississippi River from the Saint Louis of Gateway Arch fame. It is a deflated, decaying former city, now more vacant than vibrant. Twice I traveled to the city to photograph it. Only once was I detained by police there.

Burned Out Building, Sixth Street and St. Louis Avenue, East St. Louis, IL

On the morning of my second visit to East Saint Louis, I set out on foot from the parking lot of the city’s light rail station – the light rail is a transportation lifeline to Saint Louis, Missouri, connecting East Saint Louisan’s to jobs in their eponymous neighbor. I was hoping to find locals to chat with and to photograph.

After several blocks, I happened upon a stream of youth. School had let out, and before long, I was walking against a current of backpacks and teenage banter. I snapped several candid shots of students, but not until the third or fourth group did I stop and chat, and after that, only when a few brave youth finally agreed to stand still for the camera, did I take any portraits.

Students from Lincoln Middle School, East St. Louis, IL

In all, my interactions with the kids were pleasant and unremarkably ordinary. Their attention span was Snapchat length, and their interest in being photographed equally short lived. They were exactly – utterly and completely – like every other middle schooler I had ever encountered as an adult.

A block and a half after my impromptu photo session, I encountered an East Saint Louis police cruiser – which was stationed exactly a block away from another East Saint Louis police cruiser – in the driveway of housing projects adjacent to a field. Across this field tramped the straggling remains of the 2:30 school dismissal. The juxtaposition of the two cars and the field, as well as the low rise project, struck me, and so I photographed the scene. One or two quick photos, and I continued on my way. As I walked past, I gave a quick hello wave to the officer sitting in the cruiser.

Police Car and Housing Projects, East St. Louis, IL

Two steps later, I heard a loud, mechanical BLERP from the direction of the police car, which was now over my left shoulder, behind me. Two more BLERPs quickly followed, and so I walked back to the cruiser and to the officer sitting in the driver seat, his window now rolled down.

“Afternoon” I said.

“What are you doing here?” he asked.

“Taking photographs,” I said.

“Why?” he asked.

“I’m a photojournalist,” I said.

“For who?”

“Freelance.”

“Do you have ID?”

“ID for what? Why?”

“Because you are suspicious.”

“Suspicious? Why?”

He did not answer my question, he only repeated his own. “Do you have ID?” he asked.

“ID? Why? Why am I suspicious?”

“There are minor children around here, and it appears you were photographing them.”

“It appears that way because I was. I was photographing them. And I was talking to them.”

“Let me see your ID.”

I explained, as best I could, that he had no right to demand to see my ID simply because I had been photographing – and even talking to – “minors”. He explained back, as best he could, that he was demanding to see my ID and that I would be going nowhere until he was satisfied with whatever ID I could produce. To assist with this important ID check, he, still sitting in his cruiser, called for backup.

Before I could blink, a second cruiser pulled up, lights flashing, and then a third, and then a fourth. Two other officers arrived on foot. I counted six or seven officers in total. They proceeded to explain to me, in a round-robin, that I was “suspicious.” One after the other this was repeated to me, as if through sheer repetition and emphasis, I could be made to understand why I had been detained. “You are suspicious.” When I asked why I was “suspicious,” they explained that I was “suspicious” because I “stuck out like a sore thumb.”

At some point during this conversation, a sergeant appeared on the scene. He, too, explained to me that I was “suspicious” and that I shouldn’t be photographing minors. When I asked why, he first told me only that it was “suspicious,” but added that, in effect, it was suspicious because I looked as if I didn’t belong in this neighborhood.

Officer number 2, the first backup to arrive on the scene, tried to reason with me.

“Now tell me,” he asked, “don’t you think it looks suspicious to see someone from Arkansas in the neighborhood, taking pictures?” I had produced my ID by this point, revealing myself as a resident of Arkansas.

“But he didn’t know where I was from when he stopped me.” I explained, referring to the original officer in the cruiser.

“Well, you were trespassing,” said Officer Number 3.

“I was on the sidewalk, over there, and came over here when he instructed me to,” I said. Officer Number 3 said nothing further.

Minutes passed, and several checks of my background returned nothing, as I could plainly hear from the police radios arrayed about me on the hips and vests of the officers.

This should be over soon, I thought, now that I am cleared. The end was not near, however, because now an Illinois State Trooper had added himself to the cast of East Saint Louis law enforcement. His youthful appearance was reinforced by braces on both his upper and lower rows of teeth.

“Let me try to explain this to you,” he began. “You know, you look suspicious here. You stand out . . .”

“. . .like a sore thumb,” I said. “I get it, I get it, I get the subtext. But still.”

“No subtext,” he said. “You have to admit it looks suspicious to have you here, photographing kids.”

“Yeah,” jumped in Officer Number 1, “you know how this goes. ‘Hey, let me take some pictures of you. You look great. Why don’t you kids come back to my place for a photo shoot.’ and then the kids are molested or whatever.”

That struck me as unnecessarily dark and paranoid. “Well, no,” I said. “I mean, sure, I could be a pedophile, or I could entice them with candy. Or I could be wielding a bomb or something. But I’m not. I’m just a photographer.”

“You can’t just photograph minors,” he said.

“I can,” I said, “and I talked to them, too.”

Officer Number 1 did not take kindly to this line of reasoning. “Well, if you did that to my kids, I would tell you to delete them. I would take your camera and delete them myself.”

I didn’t respond. How would I?

“Where’s your car? Did you drive here?” asked the State Trooper.

“Yeah, I parked in that lot a few blocks away.”

“In the Metro parking lot?”

“Yeah, I think so.”

This apparently sparked a new train of thought in Officer Number 2. “Why didn’t you just drive around and shoot from your car?” he asked.

“And that wouldn’t be ‘suspicious’?” I thought, but didn’t say. Instead, I explained, somewhat disjointedly, about shooting wide angle. “And,” I continued, “I get out and talk to people. I shoot and I chat with people. Interact.”

I then explained at some length about the worsening divide in this country between the left and the right, about the dehumanization of out-groups, and how I wanted to show Americans to Americans again, including Americans in communities like his.

The officers heard none of it.

Officer Number 2 continued, “and what about your camera, you don’t think those guys down there at that liquor store,” he was pointing to the corner that I had yet to visit, “they aren’t going to see your camera and . . . ”

“How much is that thing worth, that fancy camera?” Officer Number 1 cut in.

I answered that it was not inexpensive, using somewhat more colorful language. “But so?” I asked.

“So you know how many murders we’ve had down there?” responded Officer Number 2.

“What color is your car?” interrupted the State Trooper, looking at my ID from multiple angles. I don’t recall my drivers license being passed to him. “What kind of car is it?”

I answered, and then the state trooper disappeared into his mini SUV cruiser, and then his mini SUV cruiser departed to the train station. We all stood looking down the road where the cruiser had vanished.

Family Leaving Metrolink Train Station, East St. Louis, IL

“You got kids?” asked Officer Number 2.

“Yep, almost 16 and almost 13.” I paused, and then asked, “you have kids?”

“Yeah, the same, 16 and 12.”

“Well, you should check out my photography project.” I had already handed him my card. In fact, I had already furnished the sergeant with my card, and, although I don’t recall when, the state trooper as well. I had also offered my card to Officer Number 1, but he had refused.

That was the extent of the personal interaction between Officer Number 2 and me.

Another stretch of time passed, with the radio cackling about a DWI stop of a UPS driver, a domestic disturbance that drew chuckles from Officer Numbers 1 and 2, and sundry other police chit chat, before the state trooper returned. He had nothing to report on my vehicle, but he did get out of the car to inform me that he was going to “run this nationally” before I would be free to go. “To be clear,” he said, “you are under” – and here I don’t recall the exact language, “perfunctory” or “preliminary” or some-such-thing – “detention, so you’re not free to go.” So I stood by.

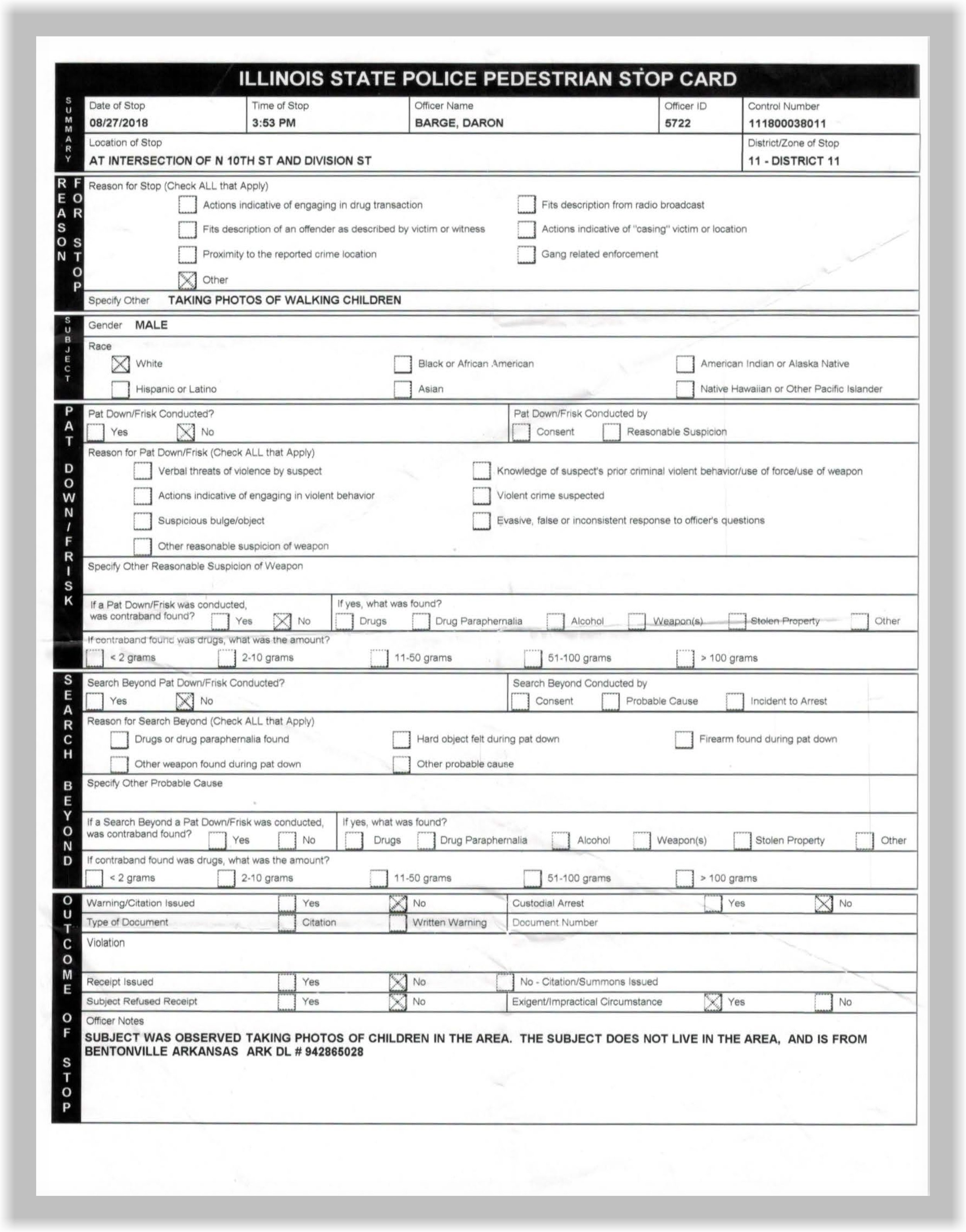

Finally, after several more minutes of fidgeting and shifting and police radio chatter, it was announced that I could leave, but not before the state trooper handed me a slip of paper. I looked at it, and saw it was a “pedestrian stop card,” a sort of receipt for my stop. It contained the details of my stop, where it occurred, what transpired, how I reacted and what the police found. It also explained, in police parlance, the reason for my stop in the first place. It said: “taking photos of walking children.” It didn’t mention my talking with them, too.

Illinois State Police "Pedestrian Stop Card” for the incident